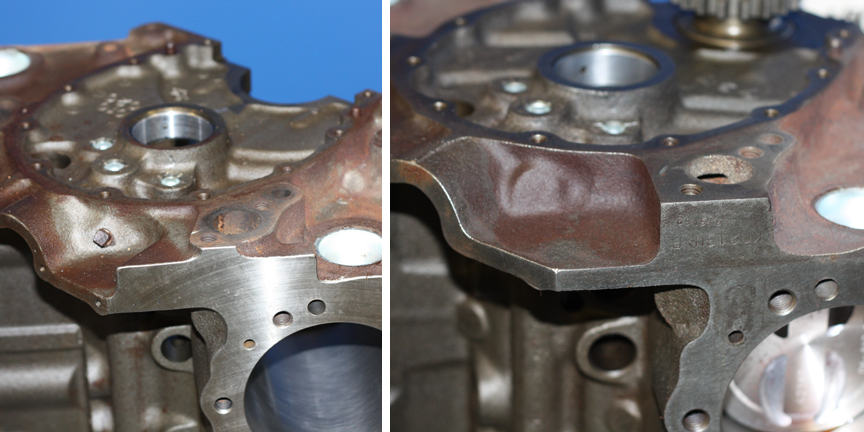

This shows the difference between the identification pads.

The pad on the right is much smaller signifying a newer style block.

In the first session we used our dyno software along with a customer interview to design our engine to meet the criteria and expectations of our customer. Now we will use that information to select our parts and create a build sheet for our project engine.

Since this is a “budget” build, we start out with a “seasoned” (used) 4 bolt main block. Some of the choices we need to decide on are, one or two-piece rear seal, light or heavy weight casting, roller or non-roller block, and whether or not we need provision for a mechanical fuel pump.

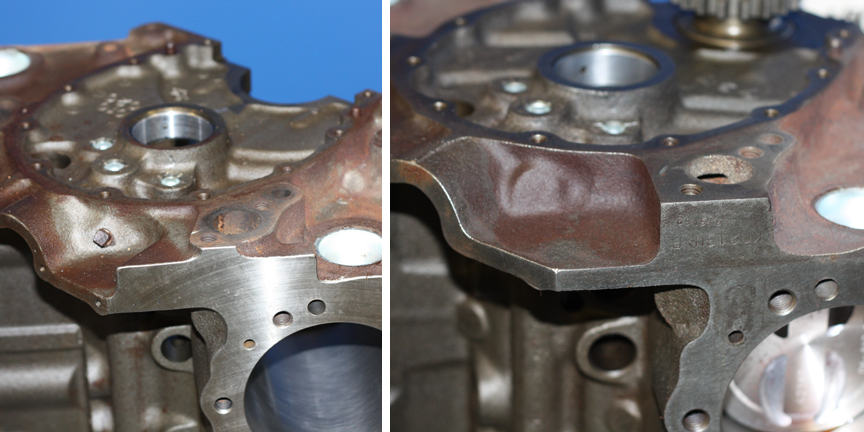

Since the introduction of the SBC in the 1950s, it has seen quite a few changes, including the shedding of considerable weight. You can immediately tell the difference by the pad above the water pump on the passenger (right) side of the block. This is the same pad the engine identification number is stamped into. This pad started out at about 4.250 inches in length. In the first weight shedding of the mid to late 70s this pad shrunk to about 1.625 inches. This also meant a loss of material throughout the block. This was done both as a manufacturing cost reduction (less iron), but also as a weight reduction to improve fuel efficiency and emissions standards. This iron diet continued with newer releases including the one-piece seal revision. This weight reduction also took place in all other components, especially the cylinder heads. We used to joke, “the only good thing about the light weight heads is that you can carry them two at a time to the scrap pile”! While you may be thinking lighter components (think aluminum) are better, the rigidity of the block can be an issue as you approach higher horsepower numbers. The necessity of a heavier casting block is more apparent under high load conditions, such as circle track or 24 hour endurance races, or even drag racing where drag slicks are used, connecting more of the horsepower to the ground. In a street car, and especially street rod use where tire spin weakens the link between the road and the engine, this rigidity becomes somewhat less important. To the other extreme, you can get into GM Bowtie blocks, or Dart, World Products, or several other after market suppliers of race quality blocks.

We have chosen to go with the medium weight (late 70s to early 80s) block since the early heavy weight 4 bolt main blocks are becoming rare, especially ones that haven’t been bored oversize already. Keep in mind this is the same block used in Camaros and Corvettes from the factory, and is still a heavier casting than GM is using for their street crate engines. Since this engine is being built to run on 87 octane pump gas, we are keeping the compression down to 9.7:1, which will result in lower cylinder pressures and will be adequate for 400 horsepower. This is one of two engines we offer using a used block, capable of running on 87 octane pump gas. All of our other crate engines are based on an aftermarket, (usually Dart) block.

All small block chevys built since 1986 with the exception of GM Performance Parts or after market performance castings, are of the one-piece seal design. Although sbc's didn’t have a rear seal leakage issue, this was supposedly an update to avoid or eliminate rear seal leaks. Since the odd shape at the rear of a two-piece seal small block crankshaft, is part counterweight, the new round one-piece seal design crankshaft has to be externally balanced at the flywheel to compensate for the lack of non-concentric weight on the earlier design. We want to stay with an internally balanced engine, or the pre 1986 two-piece seal design.

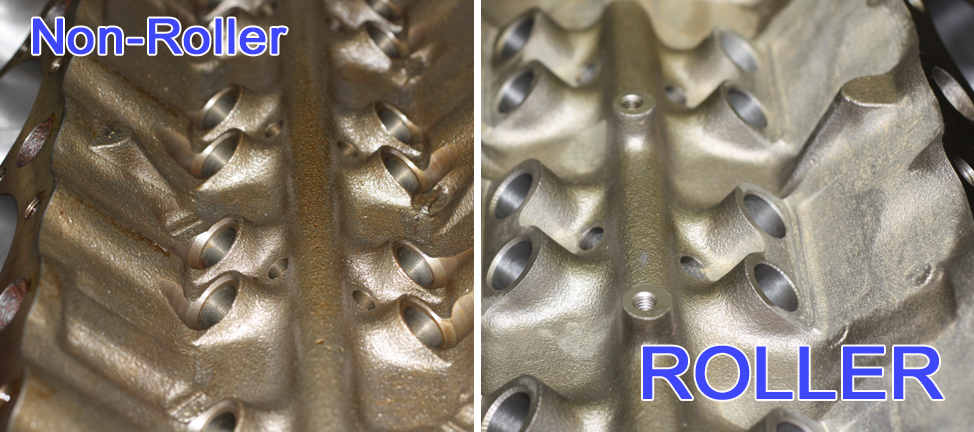

The last two considerations are pretty simple. Roller or non-roller block refers to if you need the block to be factory roller lifter ready. If you are going to run a roller lifter cam you have two choices, a block that is machined that way from the factory, or running a “retrofit” roller cam. A block machined from the factory will have taller lifter bores for the roller lifters, bosses cast in the lifter valley for attaching a lifter retaining “spider”, and the front of the block machined for a camshaft retainer plate. With all of these provisions, you can use an aftermarket hydraulic roller camshaft with stock type roller lifters. If you are using an older block without these provisions, and want to run a hydraulic roller camshaft, you have to have special roller lifters with “tie bars” to keep the rollers in alignment with the cam lobes. You also need to use a camshaft thrust button at the front of the cam to keep the cam from walking forward. Since we are going to use a hydraulic flat tappet camshaft, (non-roller) this is not an issue for our selection. Either type of block can be used with the flat tappet lifter. Other than GMPP or aftermarket blocks, there are no two-piece seal block that are factory machined for roller lifters.

The last consideration is the fuel pump provision. Since we don’t know if this engine is going to be used with an electric or mechanical fuel pump, we want the provision for the mechanical pump. The fuel pump mounting hole can be blocked off with a cover plate if it is not needed. Again, any factory block that came with a two-piece rear seal will have a fuel pump mount. If you start looking at one-piece seal block, be careful, some have the mount, others don’t, and some have the casting but are not machined inside for the fuel pump push rod.

OK so here’s what we decided for our block: