Camshaft Selection

Camshaft Selection

Last and certainly not least, we need to pick out a camshaft to use. This is generally the hardest part of planning an engine build. Granted, if everything else is right and we use a camshaft we have used in the past with good results, the customer will probably be happy. But what is best for this build, or what is the customer’s expectation? Take a look at the small block Chevy section of any cam catalog, it’s mind boggling! Combine the many choices (not counting endless custom grinds) with the fact that we are talking about many subjective issues here. The camshaft is a great deal of the “personality” of the engine. It determines where peak torque or peak power occur, how long a torque curve, how rough an idle, and many other factors. It also has to work in conjunction with other components, like the cylinder heads, to achieve our final goal. And we haven’t even looked at solid or hydraulic, flat tappet or roller yet!

Since this engine is based on one of our budget priced crate engines, we will be restricted here to a flat tappet hydraulic camshaft. On a custom build, the cam decision can be altered by what’s available in your budget. Again, since we are not building this engine for a particular customer, we need to build what will be a nice, fun to drive, set you back in the seat, put a smile on your face, engine.

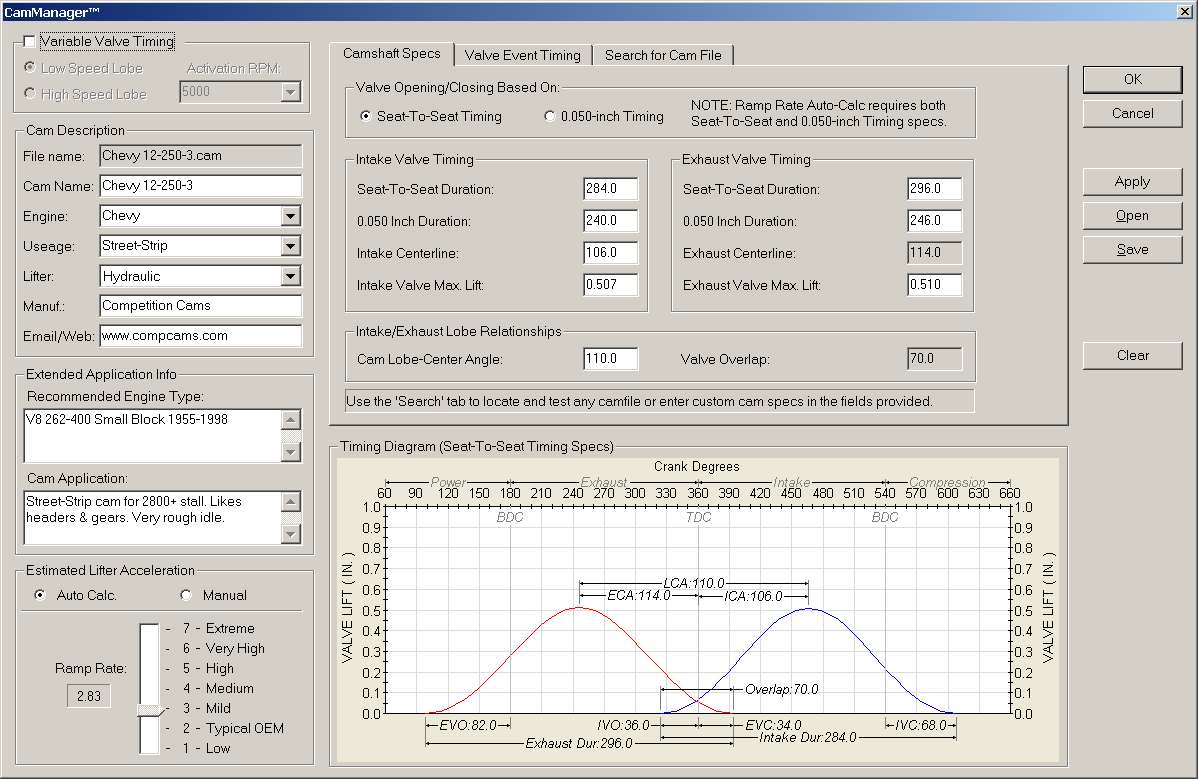

Since the dyno software we use (Dyno Sim 5) is affiliated with Comp Cams, you can purchase a cam disk with all the Comp Cams part numbers available to import directly into the software. It will also let you input cam information directly into the cam manager section if you have all the needed data. We use a lot of Comp’s cams, as well as some custom ground cams for racing applications, so you are not restricted to using a Comp Cams part number (but it is easier). We have selected a couple different cams to see what the power curve looks like. Like we did with the cylinder head selection, the software allows you to compare different parts by overlaying the curves.

As an engine builder, we are more concerned with torque numbers than horsepower numbers. While horsepower numbers provide bragging rights, torque is what you feel setting you back in the seat. As a matter of fact, torque is measured, horsepower is a calculation. Horsepower is torque times rpm, divided by 5250.

We are looking for a torque curve that would look like a table top, a long straight horizontal line that carries through several thousand rpm. We don’t want a curve that shoots up, hits a peak, and drops off. We are also looking (if this is a street engine) to see torque numbers at a low enough rpm to give good acceleration from a stop. Again we can make bigger horsepower numbers, but if the engine doesn’t come to life until 4000 rpm, it would be a good engine for the drag strip, but it’s not a fun engine to drive on the street.

The final two cams we tried had similar torque curves. Since the 12-250-3 only lost 4 foot pounds (technically pounds foot of torque, but that just doesn’t sound right) of peak torque, but that torque continued higher in the usable rpm range, resulting in 30 more peak horsepower. We are showing our numbers should be close to 486 foot pounds peak torque (475 at 2500 rpm), and 442 peak horsepower at 5500 rpm, on 87 octane pump gas.

Keep in mind this is all on a computer simulation. We will dyno this engine when it is done to get the actual numbers.

That’s enough for this week, come back next week when we will select all the components we are going to use. We will also discuss what to look for in selecting a block, and will start the machining of the block.